Monstrous Racism in Medieval Manuscripts

The term “monster,” in modern English, is a common judgmental phrase when referring to vicious and disturbing creatures. When visualizing the word through today’s definitions, ominous images of deformed beasts and demons emerge from the imagination. However, the term “monster” is also utilized when describing something or someone that can lack a sense of humanity in what they do or say. In some instances, these “monstrous” people, whether acting or fully believing, chose a lifestyle that seems so inhumane to society that they are no longer considered humans. This word, albeit just a descriptor, is also used as a hurtful phrase or slur when someone wants to label someone else as something inhumane, or different than themselves. As a result of this thought process, these inhumane people are mentally and intentionally being morphed to illustrate a bestial appearance that will either exaggerate their natural characteristics, or completely scramble them into some more evil. Throughout medieval illuminated manuscripts, the viewers are faced with monstrous beings that used to look like normal human people, and are later morphed into something out of fantasy, or could easily have been brought up from the depths of hell. In this essay, I will be focusing on the monstrous miniatures in medieval illuminated manuscripts and their connections with religious racism. This paper will also highlight the prosecution of non-Christians and their foreign lands; as well as the religious monsters that show up in religious texts to highlight their power. From monstrous portrayals of saints and demons to the demonization of an entire race, the various forms of racism and discrimination that take place throughout these manuscripts will be analyzed and picked apart to showcase a few instances of how racism and discrimination took place during medieval times.

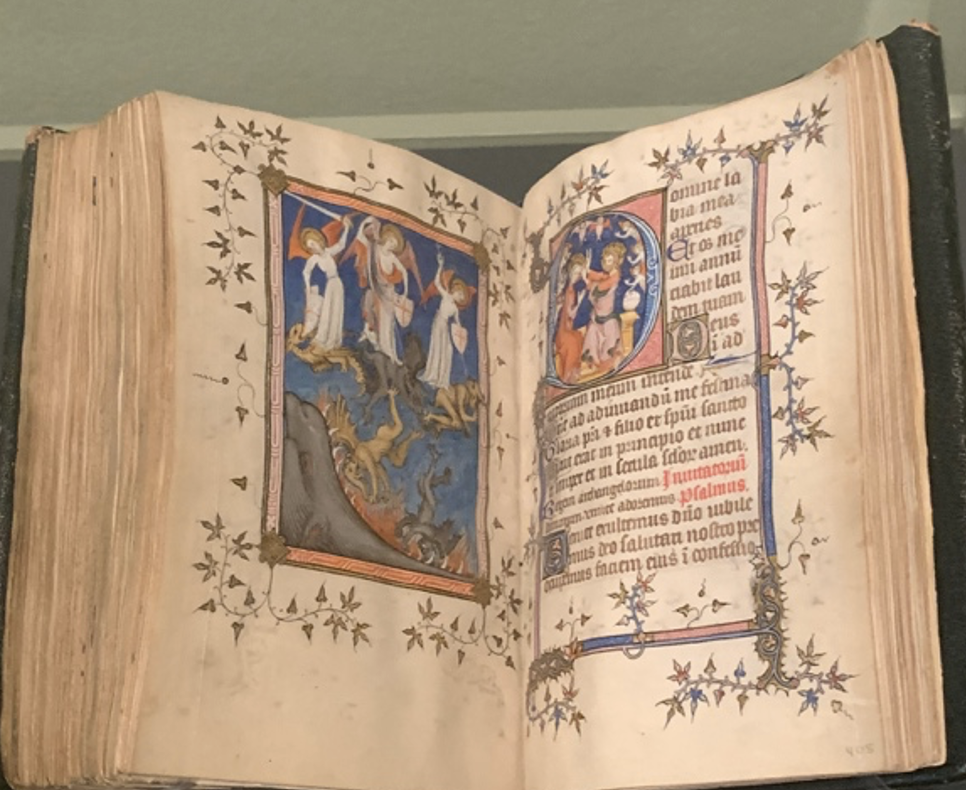

In early first century CE, racial monstrous lore became part of the Christian framework through introduction by Pliney the Elder, an influential writer among Roman history. Though Pliney spent most of his time studying and learning about natural phenomena, he also wrote arguably the most important and influential sources of information describing monstrous races and their foreign lands in detail. Later recognized and reshaped as Wonders of the East, his work told a story that illustrated these views of foreign lands and their people. These stories about monstrous races circulated throughout Latin and Old English manuscripts, and depicted various races that can now be identified in modern times, albeit a little bit skewed. During the same time period as these stories, many of the Christian followers were conflicted about the morality of these monsters illustrated throughout illuminated medieval manuscripts, and were concerned about the souls of monstrous creatures and their connections to Christian beliefs. While many of these monsters were originally created to represent and strengthen the good faith of Christian philosophies, there were also a numerous amount of monsters depicting sinners and fallen angels to showcase the overall depth of the Christian religion. Though these physically deformed beings and beasts were used as a way to describe the prejudice views of the Christian empire, many beautifully depicted and interesting stories came from them. These monsters, albeit ended with cruel intentions, helped many scholars in understanding the unspoken thoughts about lands that were new to each of these adventurists and their society. They were not all created to be ugly nor to be the antagonist of each story. According to the Bestiary, various animals were created in the image of Christ, like the unicorn with it’s horn to depict the unity of God. The illustrated monsters used in various religious texts, were utilized to display symbols of Christ and his disciples, and also to entertain the everyday viewer. In the Mostyn Gospels, for example, monstrous detail was utilized to express the concept of divine inspiration through the book of Luke. In this specific miniature, Luke is hoisted atop his symbolic ox, and writing, presumably, the Gospel of Luke. However, while this description does not sound all too monstrous, the unusual features that the ox holds are enough to morph this common animal into something more mystical and “monstrous.” The illustrator of this particular gospel emphasized not only the size of the everyday beast, but also attributed wings and a halo to this beast’s overall appearance. Signifying that both beings are divinely entwined, this particular illumination was used in a nicer way than most. The more cruel take on monsters is shown in the Psalter Hours of Yolande de Soissons, where hell is depicted as a monstrous beast with a massive mouth, devouring the cast down rebelling angels. Thrown out by Saint Michael, the lesson for the viewer is plain and simple; do not stray or you will be cast out, like the unforgivable angels – now demons. While the divisions from good and evil are clearly stated here, it couldn’t have been portrayed much different. More importantly, some illuminations were created to portray foreign travelers and other religious believers as monstrous beings that were encountered through explorations and stories. These, specifically, were monsters created out of hatred and the fear of the unknown. Some of the more common monsters to come out of these adventure stories, were from the tales of Alexander the Great. Transformed through exaggerations and misheard recounts of travel tales, monsters throughout the medieval period only grew worse with tales of Alexander the Great. He travelled throughout most of Greece, Turkey, Egypt and India through the fourth century, and recounted stories of romance and history through his triumphant return. Unfortunately, albeit wonderful adventures fables, Alexander the Great’s stories of gallant encounters and triumphant wins never really aligned with that of the real world. From battling cyclopes in Northern France or Southern Netherlands, to killing bloodthirsty beasts like dragons and tri-horned beasts, the overall imaginative exaggeration is taken to the highest level. Alixe Bovey rationalizes that these “monsters were often used to define boundaries and to express a distinction between morality and sin – or conformity and nonconformity.” Bovey believed that monsters were illustrated with the degree of sin in mind, and were adjusted to fit the crimes of the sinners. Plainly speaking, the more sinful the crime, the more deformed the monster.

Early on, the metaphysical monsters displayed in medieval manuscripts were created solely to express any physical or spiritual dangers that may have occurred during travels throughout the medieval period, such as dangerous grounds or people that others may come into contact with. However, during the twelfth century, the Christian church decided to exclude Jews from the sacred grounds, claiming them as heretics. Afterword, some of these monsters that were based on real animals that people had seen or talked about, molded into monsters that inhabited symbolic expressions of ideas given by society to interpret. While some of the monster miniatures can resemble forms of animals and humans, some are purely and fictionally monstrous, combining multiple features from various different animals or folklore. These more wildly fantasized versions of monsters tended to be less believed as real, and more for pure comedic relief. Some of these comedic reliefs, however, would not be categorized in the same comedic fields that we use today, rather more erring on the side of dark racist humor. In the Byzantine Psalter, for example, monstrous imagery was commonly utilized for demonizing foreign people and their many different religions. Inscriptions of this psalter by Monk Theodore, illustrate Christ surrounded by dog-headed creatures (named cynocephali) whom are assumed to be interpreted as Hebrews and labeled “Hebrews are dogs.” Supposedly, this is to be a take on Psalm 22:16, “For dogs have surrounded me; A band of evildoers has encompassed me; They pierced my hands and my feet.” While the miniature does show the dog-like creatures, the interpretation that the Hebrews were in fact evildoers, is a bit of a stretch to appease Christian beliefs. While this is not the only instance where non-Christians are portrayed as evil, in a few other Books of Hours, the take on Jews becomes slightly less monstrous and more judgmental. The illuminator illustrates in one example from 1204. that the enemies of Jesus, Jews, are no different but by their hats and appearance. In another example, the same judgment is expressed through the only physical difference in their demeanor of furious faces and dramatic expressions. While all of these are examples of the judgmental representation of Jews and other non-Christians, these humans were thought to be monstrous for denying Christ and believing in something different than Christians in general. Because of their religious views, their features were exaggerated with various different forms of deformities and sometimes even cannibalism. Most times, Jews were outcast in each Book of Hours, and alienated in their appearance; sending the message that if they looked different, they were different.

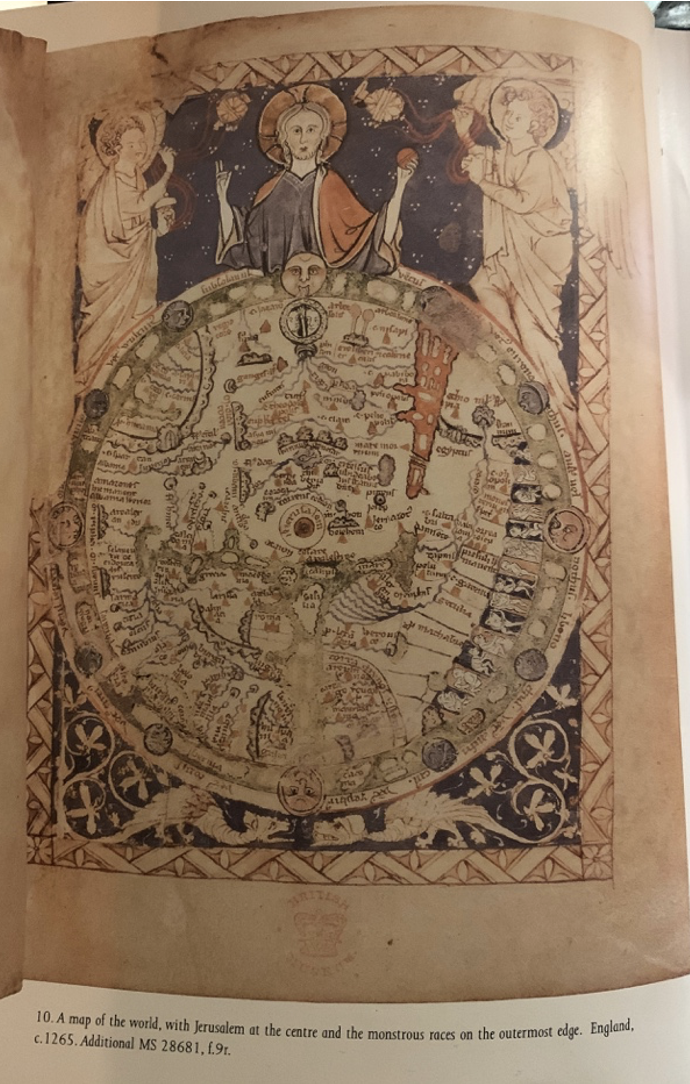

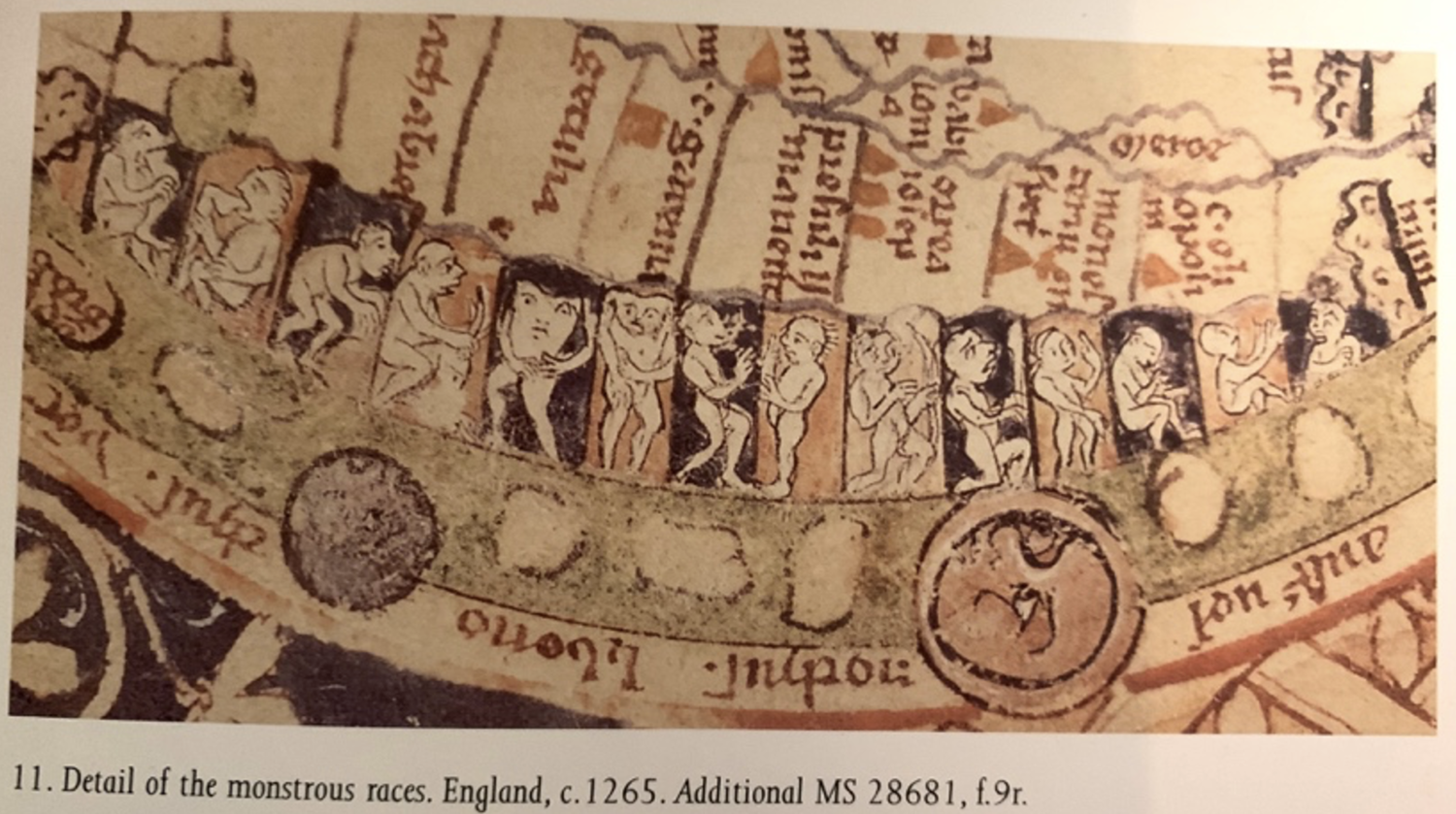

Although Judaism was the number one monster in most Christian texts, there were also instances of entire races being ostracized and demonized through medieval illuminations. In the French manuscript Livre des merveilles du monde, there is a large half page miniature showcasing what is supposed to be medieval Ethiopia. In this illustration, many of the Ethiopians are either displayed as naked or clothed in what looks to be animal skins. For the Christian beliefs, this is an openly committed sin that goes back to the casting out of Adam and Eve. Displayed in various places, the viewer can see naked men crawling on the ground and even women, conversing with other members of their tribes fully nude and carefree. From eating lizards and worshiping a canine idol, the alienated people of Ethiopia, are viewed as “a world turned upside down” and “monstrous” for rejecting the European social standards. Asa Mittman and Sherry Lindquist wrote that “Monstrous imagery was often associated with members of socially disadvantaged groups in order to suggest that they were less than human.” The representation of these groups throughout medieval times, coincides with the thought process that all others that seemed too physically different, mentally impaired, or just thought differently than the Christians were considered monstrous and portrayed as such. Each monster was created with their muse in mind, and each was more deformed depending on the severity of their sins. In another Psalter manuscript from 1265. England, a miniature map showcases various monstrous races from a Christian view point. In this map, continents, natural landmarks, and some cities are identified in Latin labels. Already physically and metaphorically higher in status than the world, Christ is illustrated overseeing his earthly kingdom from a heavenly view point, along with two angels at his side. Below the world, in the region of “hell,” sit two dragons, as if they are holding up the globe with their own heads, seemingly being crushed by the weight of it. At the center of this map, resides Jerusalem, the holiest of lands in medieval times. Towards the right edge of this map, the illustrator highlights Pliney’s influence on the monstrous world by illustrating various monsters from the Wonders of the East. Standing a no more than a centimeter tall, the fourteen different described monsters are casted out into a shadowing and darker edge of the world, as if they are not to be touched, but feared.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bovey, Alixe. “Medieval Monsters: from the Mystical to the Demonic.” The British Library, The British Library, 17 Jan. 2014, www.bl.uk/the-middle-ages/articles/medieval-monsters-from-the-mystical-to-the-demonic.

Bovey, Alixe. Monsters and Grotesques in Medieval Manuscripts. British Library, 2002.

Camille, Michael. Image on the Edge: the Margins of Medieval Art. Harvard University Press, 1992.

Lindquist, Sherry C. M., et al. Medieval Monsters: Terrors, Aliens, Wonders. The Morgan Library & Museum, 2018.

Paolo, Giovanni Di, and John Pope Hennesey. Paradiso: the Illuminations to Dante's Divine Comedy. Thames & Hudson, 1993.

Randall, Lilian. Images in the Margins of Gothic Manuscripts. University of California Press, 1966.

Thimann, Heidi. “Marginal Beings: Hybrids as the Other in Late Medieval Manuscripts–By Heidi Thimann.” Hortulus, 15 May 2013, hortulus-journal.com/journal/volume-5-number-1-2009/thimann/.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

“Mostyn Gospels, in Latin.” England, perhaps Gloucester. Circa 1130. (MS. M 777, fols. 37v-38r).

“Jesus and crowd”, Book of Hours, in Latin and French. France, perhaps Verdun and Paris, circa 1375. Illuminated by the Master of the Jean de Sy Bible. (MS M.90, fols. 48v-49r).

“Psalter Hours of Yolande de Soissons, in Latin.” Amiens, France, circa 1280. (MS M.729, fols. 404v-405r).

“Creating Enemies” Book of hours, in Latin and German. Germany, perhaps Bramber, circa 1204-19. (MS M. 739, fols. 22v-23r).

“Livre des merveilles du monde, in French.” Angers (?), France, circa 1460. Illuminated by the Master of the Geneva Boccaccio. (MS M.461, fols. 26v).

Christ among dog-headed men.” Constantinople, 1066. (MS 19352, f.23.r)

“A map of the world, with Jerusalem in the center and the monstrous races on the outermost edge.” England, circa 1265. (MS 28681, f.9r) + Additional detail image