Pollock vs. Masculinity in a Post-World War II

Known for his “drip paintings,” Jackson Pollock created an atmosphere of art that was not only wildly progressive, it was also vastly romanticized for its time. While it is important to cover the idealized view of romantics in the studio, it is also important to discuss what all these principles and views entailed when discussing post-war artists of this time. During the period that Pollock’s work was starting to be recognized, the visuals from the war and the concentration camps were starting to embed themselves into the minds of society. Viewers who were enthralled with Pollock’s fascinating method and style, fed the flame of interest to a point that it almost seemed obsessive, in an attempt to redeem humanity’s destructive nature. Though most viewers don’t take in to account the process in which Pollock went through to create his famous paintings, the suffering and mental changes that precursor the creation of these paintings are just as important. Born into a very large family of small-town Cody, Wyoming in 1912, Jackson Pollock was the youngest of five sons. While his childhood was considered fairly abnormal for the time, it is easy to pinpoint the shifts of his artwork in his timeline previous to the war as well as after. Not only did Pollock grow up with an absent father, his upbringing and masculinity was shaped through the dominant nature of his mother and the twists and turns of all of his siblings and teachers. During the important mental and artistic creation of a young adolescent man’s mind, it is crucial to notice these influences; and even more so during post war creations. Throughout this time that Pollock is shaping the ideas and methods of his artwork he is in the midst of alcoholism and taken under the wing of his teacher Krishnamurti and his vast theosophical teachings. Krishnamurti’s mentorship for Pollock later influences the shamanistic ideals that he inherits, essentially turning him towards the communist circle. Coincidentally for Pollock’s type of nontraditional art, many of the issues he faced during his adolescence and teachings pushed him to the top of the art world singlehandedly, and thus reintroduced society towards peering back into the studio practices of the modern artist. While many artists at the time were struggling with their identities post the cataclysmic war, the shift of masculinity in art is best described through the work of Jackson Pollock’s “Mural” of 1943 when he shocks the world with his image defying techniques and size (Figure 1).

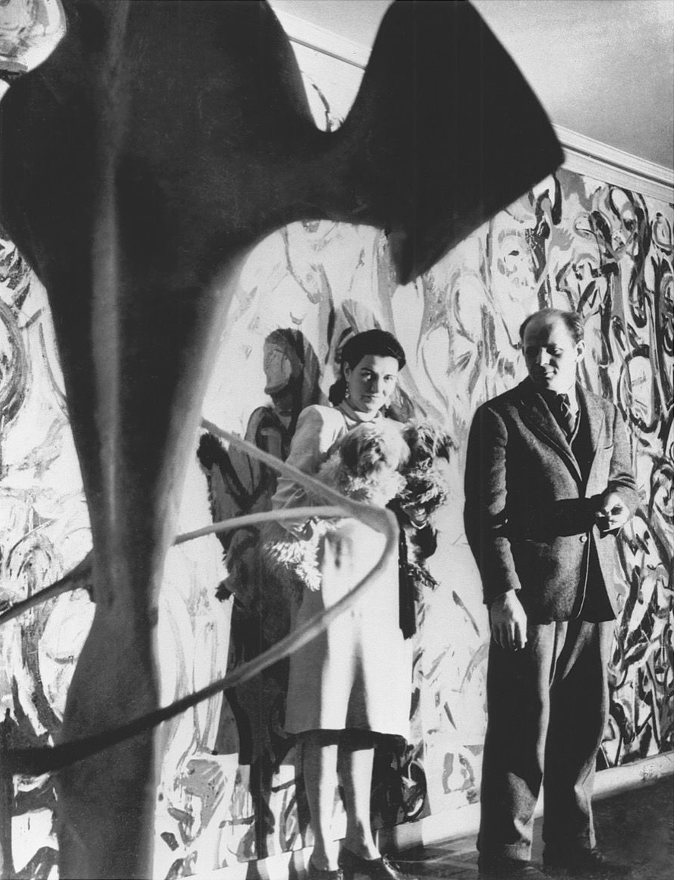

Recognized as a transitional time from his primal easel paintings towards his famous drip paintings, “Mural” of 1943 is considered the first of Pollock’s to showcase the radical technique changes in his art; also known as “Pollock’s œurve.” Measuring at the massive size of 8ft by 20ft, this painting was the first in his large-scale work to be brought into existence that ignores both the human scale and figuration and meant to be viewed in close proximity. As commissioned for Peggy Guggenheim’s front foyer, the monumental dimensions of this painting were actually the size of Guggenheim’s foyer wall and was the biggest of all his mural sized paintings (Figure 2). Having torn down a wall in his own studio to create this massive piece, the most famous myth of him completing it in one legendary, booze-filled night seems as audacious as it is mind-blowing. A claim curated by Lee Krasner, Pollock’s wife, and advocated by Guggenheim’s memoirs, this myth has been debated by numerous art historians and fanatics. Though various analyses describe multiple layers of dried paint and oils that could determine that this might have been a false accusation. Some historians argue that the imaging of paints reveal a compositional structure that both the brown paints and other diluted colors were done at the same time. From these analyses, it is easier to believe that Pollock initially sketched the first phase of this piece with some emotionally filled brushstrokes of color prior to the detailed defining color of browns. These contrasting colors of dark browns, blues, yellows, reds and a combination of more cover this canvas in a somewhat intertwining mixture of shapes. While some can interpret a faint hint of humanity in this painting, it is difficult to pinpoint the exact form in which these figures take. Thus, spiraling into Pollock’s rejection of humanity in his paintings from here on out.

Four times larger than any other paintings of his, Pollock’s “Mural” unleashes an emotional force that was never able to be seen prior to the war. Post World War II, and all the disaster that befell society, many artists, including Pollock, felt the urge to rethink the way they were creating art, and what exactly art meant to society. Harold Rosenberg, an art critic and philosopher, once defined painting as an act, and declared the process of making art to be considerably more significant than the finished picture itself. Jackson Pollock, who was later deemed an “action painter,” followed this philosophy throughout his creations by making them about the process versus the end result themselves. In an attempt to explore the creations of his paintings, Pollock’s masculinity is found in the way he frees himself from the restraints of a plan and human nature. Pollock takes away the order of what would be considered painting rules and breaks through the barriers with force, as if he was breaking through the terror-driven society post war. James Johnson Sweeney describes this breakthrough as “volcanic.” He celebrates him by defining this work as “unpredictable, undisciplined, and lavish, explosive, without an ear to what the critic or spectator might feel. Painters who will risk spoiling a canvas to say something in their own way, Pollock is one” (Emmerling, 46). By abandoning humanity and the objective reality, many artists like Pollock started to focus on the emotions left behind from the war and how to utilize and externalize them into their artworks. Because emotions are far more of a fluid gesture, many of the artists during this time began to showcase these gestural methods in the abstract art world. While more sporadic changes in Pollock’s work featured odes to other abstract painters such as Pablo Picasso and Mark Rothko, he still seemed to struggled with the idea of art and masculinity in his own mind and work. In a description of his painting “Mural,” it is said that, “although [it was] influenced by his earlier work in this format, Pollock struggled to control the composition” (Artstory). They continue on to say that, “he incorporated decorative patterns in thinly brushed paint to achieve an intimate pattern within the grand scale” (Artstory). Given the state of society post war, it is easy to focus on Pollock’s well-known struggle with alcoholism in the creation of these masterpieces. However, the lesser known information regarding his masculinity and his struggle to redefine what art and humanity meant to him is a greater example of how his drip paintings and mural came to fruition.

Prior to Pollock’s œurve, the restraint held within his paintings is significantly more prominent. For example, in Pollock’s work “Going West” from 1934, the stylistically narrative subject shows strong influence from early muralists that he studied during his time at the New York Art Students League just a few years prior. In this painting viewers are able to notice the similar masculine and gestural brushstrokes, Pollock used in creating this narrative scene. While more obviously this painting is very clearly still inclusive of humanity, it is also noted that humanity is still blurred and less of a main character here. Other examples of romanticized practices includes that of Morris Louis, for his gravity pieces like “Saraband” (Figure 4). Louis created a series of these gravity-driven “poured paintings” throughout his career, which he would later call “Veils.” This practice was inspired by the same inspirations of Jackson Pollock and Helen Frankenthaler, and soon would be lumped into the same romanticized ideas that viewers entangled with the formers. In a post-World War II era, so disturbed by humanity and the outcomes of concentration camps, it only makes sense how these artists and viewers dove towards more nature driven pieces and the exclusion of humanity. While these new, so to speak, Impressionists were not aiming to be the forefronts of a radical shift, the reality of their new tagline could not be removed until artists like Bruce Nauman.

Bruce Nauman’s influence, while widely celebrated for his various sculptural, performance, and video works throughout the 1960s and onward is a prime example of the hardships that masculinity in art still struggles with. While the subject of his works range from morbid scenes of death and hardships of life to confusing sexualities and open spirituality, the important transformations he has made in political and societal movements are some of his biggest accomplishments. Nauman, like most American based artists at this time, spent his formative years in the midst of political conflicts of the Vietnam war, Civil Rights, and Women’s Rights movements. Similar to Pollock, Nauman’s art reflected a lot of the conflicting emotions he had towards the ideals that were once considered artist “standards” and model practices. For example, Nauman’s video installations and performance art concentrated on expanding artistic boundaries and creating art for the sake of creating art, rather than forming to what was more common in the art scene at this time. In turn, this way of practice forced Nauman towards the conflicts of romanticizing studio practices and sought to deromanticizing the ideas that artists were held to like the beautification of creating an art piece like Jackson Pollock or Morris Louis.

Nauman’s piece “Dance or Exercise of the Perimeter of a Square”, commonly known as “Square Dance,” is a great example of the deromanticizing of studio practices and the reestablishment of what it means to be a masculine artist. In this particularly short black and white video art piece, Nauman documents an area in his studio that is just big enough and bright enough to view himself and a corner of his work space. In frame, you can see the shape of a square taped to the floor of his studio with smaller pieces of tape positioned in the middle of each side. The video starts with this square in view and Nauman standing on the farthest side, facing opposite of the camera. Shortly after, Nauman starts his sequence by alternating his feet to tap each corner of the line he is standing on. He does this motion thirty times on each leg, before reaching across to face another side of the square and repeating the process counter-clockwise. Nauman continues this process on each side of the square, and then repeats it backwards by continuing clockwise. Visually speaking, Nauman’s studio is anything but romantic, and this short clip is horrendously monotonous. However, the conceptual commitment of Nauman’s idea is enough to make you want to dissect it. Whilst the video is documented in black and white, and the area he is working with is clean, the viewer’s eye is almost drawn to the surrounding area of materials haphazardly thrown about. This doesn’t necessarily distract from what Nauman is doing, however the sheer boring nature of the video lets your eyes wander to different areas of the studio.

Going back to Pollock’s painting of “Mural,” he takes to expanding this idea of expressionistic work and creates his idiosyncratic technique of “drip painting” and pouring paint onto canvases, horizontally laid on the floor. Unlike “Mural,” which was painted vertically, Pollock’s interest in the physicality of paint and material becomes more prominent. This shift of technique signifies the pivot away from previous figuration towards pure abstraction. His inclusion of non-traditional studio paints, such as enamels and house paints and more, pushed Pollock further into the practices of Abstract Expressionism and redefining his masculinity within his art. Whether these materials were thrown onto the canvas surface or were planned specifically, each creation was one step further into perfecting and encompassing his technique. As Pollock used to say, “Painting is a state of being… painting is self-discovery. Every good artist paints what he is.” Hal Foster once said that Nauman’s art was “more of an activity and less of a product,” for the viewer (Foster, 2). Moving along with the postmodern movement, Nauman’s view on the new impressionist was deemed ridiculous. Postmodernism, in contrast to modernism, critiques the ideas that modernist ideas that are laid out by modern artists such as Pollock and Louis. In a way, they are made to be impersonal, whereas modernist art is overly personal. Bruce Nauman’s work “Square Dance”, not only takes away the fantastical view of an artist’s studio, it also takes away the romantic view of watching an artist at work and bringing back a masculine example of non-emotion. Similarly shown in Richard Serra’s “One Ton Prop (House of Cards),” molten lead and industrialize materials establish a forceful appearance of the fragile idea of masculinity and the struggle of finding a balance between art and masculinity. Serra states that “even though it seemed it might collapse, it was in fact freestanding. You could see through it, look into it, walk around it, and I thought, ‘There’s no getting around it. This is sculpture.’” While this piece was created long after Pollock’s struggle, the words that Serra states can be a mantra for all the male artists struggling to find their masculinity in an artist world.

FIGURES AND EXAMPLES

Figure 1: Mural, 1943

Figure 2: Jackson Pollock with Peggy Guggenheim, showcasing “Mural” 1943

Figure 3: Jackson Pollock’s “Going West” 1934

Figure 4: Morris Louis “Saraband”

Figure 5: Richard Serra “One Ton Prop (House of Cards)”

WORKS CITED

“Jackson Pollock Paintings, Bio, Ideas.” The Art Story, www.theartstory.org/artist-pollock-jackson.htm. Emmerling, Leonhard. Jackson Pollock. Taschen, 2003.

Foster, Hal. “LRB · Hal Foster · At MoMA: Bruce Nauman.” London Review of Books, London Review of Books, 20 Dec. 2018, www.lrb.co.uk/v40/n24/hal-foster/at-moma.

Posner, Helaine, and Andrew Perchuk. The Masculine Masquerade: Masculinity and Representation. MIT Press, 1955.